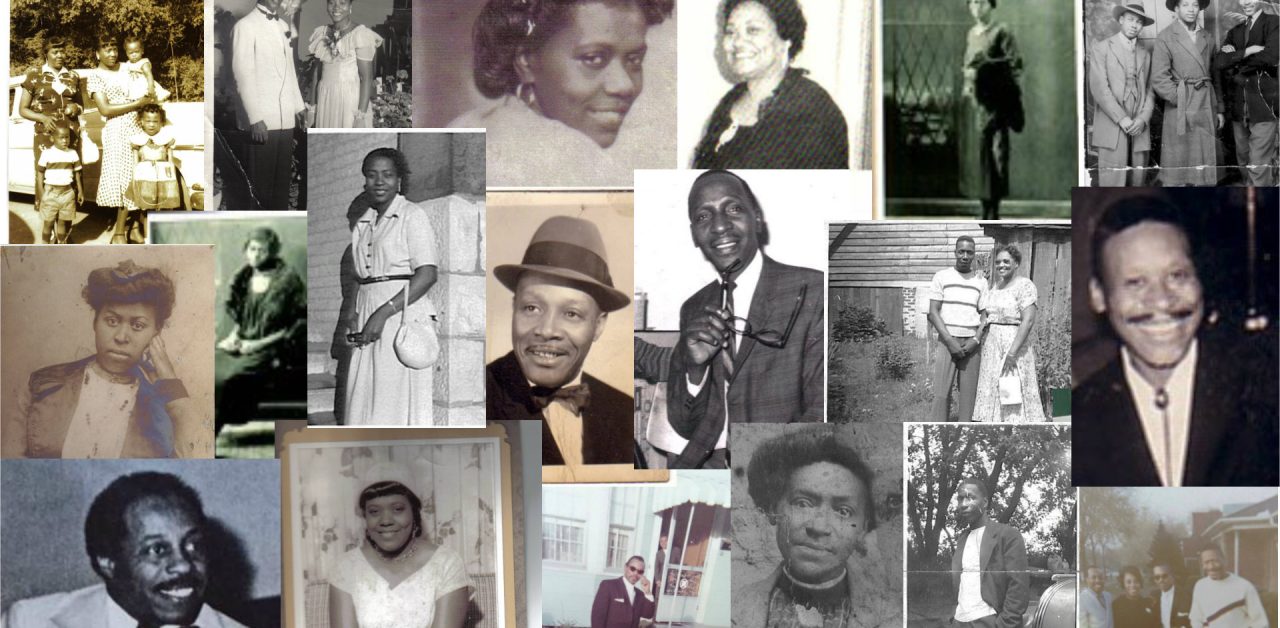

As a genealogist, I’ve spent decades searching for the stories of my ancestors, especially those whose lives were almost erased from history. Each discovery is both a victory and a heartbreak because the documents that prove their existence often reveal the injustices they endured.

This Fourth of July, as America celebrates freedom, I find myself thinking about Johnson Neal. Though I haven’t yet proven he is biologically connected to my family, I consider him part of our story. He was enslaved in Franklin County, Georgia, by a man named John M. Neal – the same name I found linked to my direct maternal ancestors. His life and service offer a stark contrast to the ideals of liberty we honor today.

Born Into Bondage, Fighting for Freedom

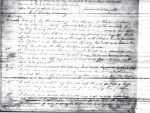

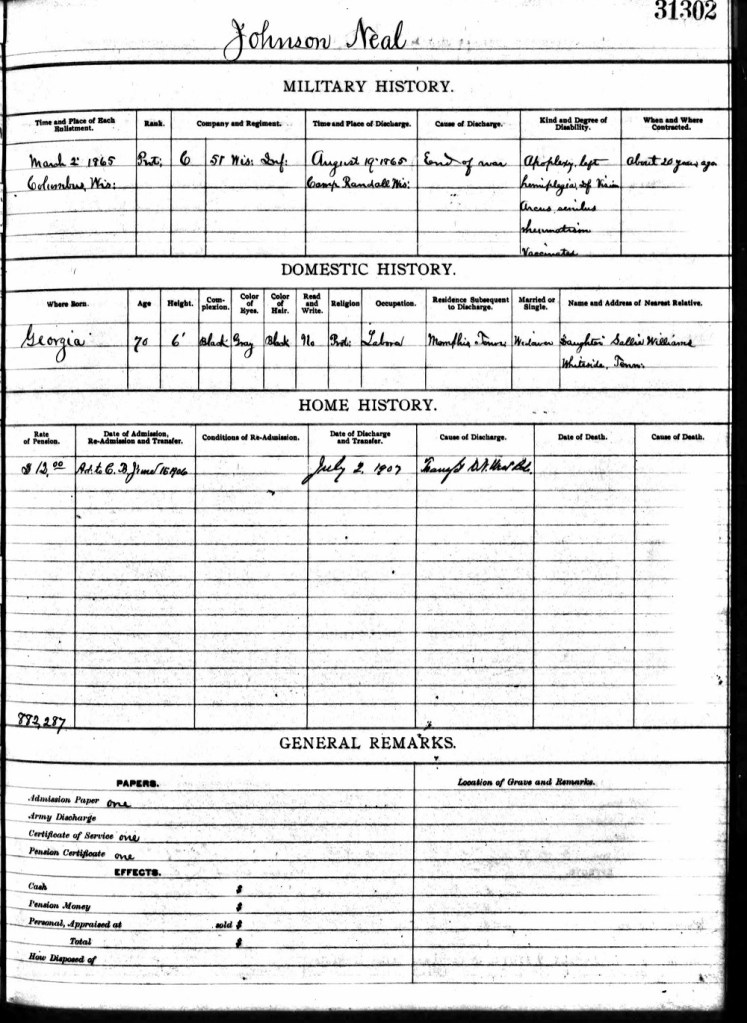

Johnson was born enslaved in Franklin County, Georgia. No record of his birth exists; like so many others born into bondage, his age was never documented. In his later years, Johnson swore under oath that he had no record of his age and could only name his master – John M. Neal – as proof.

As General Sherman’s army carved a path of destruction through Georgia in his infamous March to the Sea, enslaved people like Johnson watched plantations burn and felt the first tremors of freedom.

But liberation was uneven. Some enslaved men followed Sherman’s troops, seizing the chance to escape. Did Johnson do the same? Or was he carried North by other means, perhaps as a servant or laborer, until he found the opportunity to enlist?

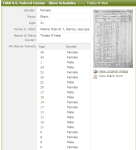

His records are silent on how he reached Wisconsin, but there, he was drafted into the 51st Wisconsin Infantry, Company C – one of more than 450 serving in the state.

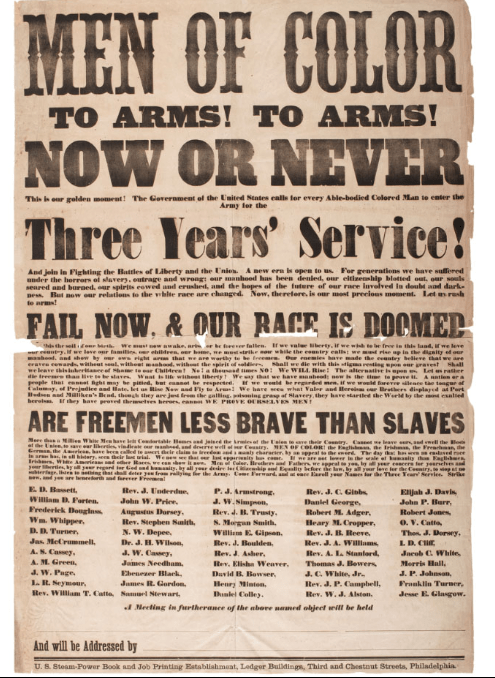

The Courage of Wisconsin’s Black Soldiers

When the Civil War began, African Americans were barred from serving as soldiers. Some worked as non-combatant laborers in Union regiments. That changed on January 1, 1863, when President Abraham Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation made it possible for Black men to enlist. Over the next two years, 272 Wisconsin men of color joined the Union army. Another 81 Black men from other states, enlisted in place of white draftees, were credited to Wisconsin’s rolls, bringing the total number of Wisconsin’s Black troops to 353.

These soldiers were often relegated to labor-intensive duties: guarding railroads, repairing supply lines, and policing the Reconstruction South. Yet they wore Union blue with pride, staking their claim to liberty in a country that had long denied their humanity.

A Life of Struggle and Resilience

After the war, Johnson settled in Covington, Tennessee, where he lived with his family until 1906. His health began to fail, and he entered a Soldiers’ Home in Ohio before transferring to Wisconsin’s Northwestern Branch of the National Home for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers in 1907.

Black veterans were welcomed at the National Home, but segregation still ruled its halls. African American members lived in separate quarters and ate at different tables. By 1900, only 2.5% of veterans in the National Home system were African American, even though nearly 10% of Union soldiers had been Black. For many, the prospect of segregated facilities and the bitter reality of racism discouraged them from seeking refuge there.

In 1910, Johnson was one of only about ten African American veterans among more than 2,000 men at the Milwaukee Soldiers’ Home. Surrounded by men who could not have known the double battle he had fought – against the Confederacy and against racism – he must have felt profoundly alone.

The Pension Fight

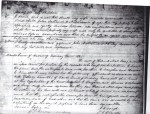

When Johnson applied for the pension he had earned through service, he faced a cruel irony. Sworn under oath, he explained that he could not provide proof of his age because he had been born enslaved and no record of his birth existed. To receive the recognition he had earned as a soldier, Johnson still had to rely on the words of the man who once owned him.

In 1912, Johnson chose to leave the Milwaukee Soldiers’ Home. His discharge papers read simply “OR”: Own Request. He returned South to live with his daughter, who cared for him in his final years and later paid for his burial when he died in 1915.

After his death, his daughter took up his fight, writing letters to the government, hiring a lawyer, and refusing to let her father’s service be erased.

A Legacy of Freedom Deferred

As I read the letter that first named him as a slave, I feel the weight of it all. For decades, I searched for proof that Johnson was part of my family’s story. Finding that letter was a triumph, but it was also a reminder that men like Johnson had to claw their way toward recognition – first as soldiers, then as citizens, and finally in the fragile memories of descendants like me.

Today, Johnson lies buried in Southern soil, near the daughter who loved him fiercely. And as fireworks light up the Wisconsin sky, I think of him marching in Union blue, a man who crossed Georgia’s burning fields seeking freedom, only to find it deferred.

Find Out More!

Are you interested in more stories like Johnson Neal’s – stories of resilience, discovery, and the hidden lives of our ancestors?

👉 Subscribe to GeneaGrams, my genealogy newsletter, for exclusive insights, tips, and family history case studies!